Hexagonal Architecture

An implementation guide

Chapter 1: APPLICATION DESIGN

To Thomas Pierrain. You are not alone, all together we will win

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Introduction

- The example application

- Designing process

3.1. Identify actors

3.2. Identify ports

3.3. Add adapters

3.4. The whole picture

3.5. Driver ports - Analogy with use cases

- Links

1.- INTRODUCTION

This article is the first one of a series showing a way of implementing an application conforming to Ports and Adapters pattern, also known as Hexagonal Architecture.

This series has a practical sense. It is supposed that the reader already has theorical knowledge about concepts regarding hexagonal architecture, like actors, ports, adapters, etc. Otherwise, in the Links section you can find resources to read about it.

In this chapter, we will see a process for designing the application, explaining how to find out the different elements of the architecture for the application we want to build.

First of all, I describe the application that will be used as an example along this series. And finally, as a bonus track, I will show an outline of the paralelism between hexagonal architecture and use cases.

2.- THE EXAMPLE APPLICATION

We will develop an example application called BlueZone, that allows car drivers to pay remotely for parking cars at regulated parking areas in a city, instead of paying with coins using parking meters.

When car drivers want to park their car, they have to get a parking permit, providing the ending datetime of the permit period. The starting datetime is the one at which the permit is requested. The application calculates the price of the permit, according to the number of minutes of the period, applying the rate of the area where the car is parked. Payments are done with cards, using a remote system.

Once car drivers have paid, the application issues the parking permit, that allows them to park the car during the period of time they have paid for. Permits are stored in a database.

The application won’t allow to get a permit for a rate if there already exists an active permit for the same rate. The car driver will have to wait for the active permit to expire in order to get another one.

Car drivers will access the application using a Web UI (User Interface).

At any time, parking inspectors can check the plate of any car parked at a regulated area. If the car doesn’t have any active permit for the rate of the area, they will issue a parking fine warning.

Parking inspectors will access the application using a terminal with a CLI (Command Line Interface).

About rates:

A regulated parking area has a rate, and there maybe different rates in a city. Rates are provided by external data files. A rate includes the following information:

- Name of the rate.

- Amount of money to pay per hour.

- Minimum and maximum number of minutes allowed to pay for.

- Timetable that defines time intervals when the rate applies, depending on the day of the week. Out of those intervals, parking is for free.

For the sake of simplicity, we’ll do the following assumptions:

-

When requesting a permit, the car driver won’t be warned about how much it will cost before issuing it. The application will charge the price to the payment card and will issue the permit.

-

Payments are performed calling the remote system synchronously. It could be possible that a payment was succesful, but then the permit issuing failed. In real life, an scheduled process would be launched to refund these transactions. In the example application, this refund process won’t be implemented.

-

Regarding parking inspectors, the example application will just implement the car checking. Parking fine warnings won’t be managed by the application.

The URL of the GitHub Repository with the application source code is: https://github.com/jmgarridopaz/bluezone

3.- DESIGNING PROCESS

In this section we will find out the elements of the architecture for the application that we are going to implement, and we will define in detail the driver ports, i.e. the API of the application.

The steps of this designing process are:

- Identify actors

- Identify ports

- Add adapters

- The whole picture

- Driver ports

So that finally we should have the following information, that could be considered the output of this process and the starting point for the next chapters:

- A diagram showing the components of the system: Hexagon (with ports), actors and adapters.

- Driver ports in detail: Input, output and description of driver ports operations.

We will not define driven ports in detail yet, since we will find out their operations later on, as we develop the business logic.

Now let’s see these design steps…

3.1.- IDENTIFY ACTORS

-

Draw an hexagon. It represents the application, the business logic.

-

Put driver actors outside the hexagon, on the left side. Drivers are those who need the application for achieving their goals. They trigger the communication with the application. As Alistair Cockburn says in his talk Alistair in the Hexagone, think of the application as a thing resting in a quiet state, doing nothing. When the driver needs the application to perform an action, the driver would kick it and wake it up saying “Hey you, do this”.

-

Put driven actors outside the hexagon, on the right side. Driven actors are those who are needed by the application for achieving application goals. The application triggers the communication with the driven actors.

In next chapters, we will see that the triggering of the conversation has to do with dependency knowledge, in the sense that the one who triggers the interaction has to know the dependency.

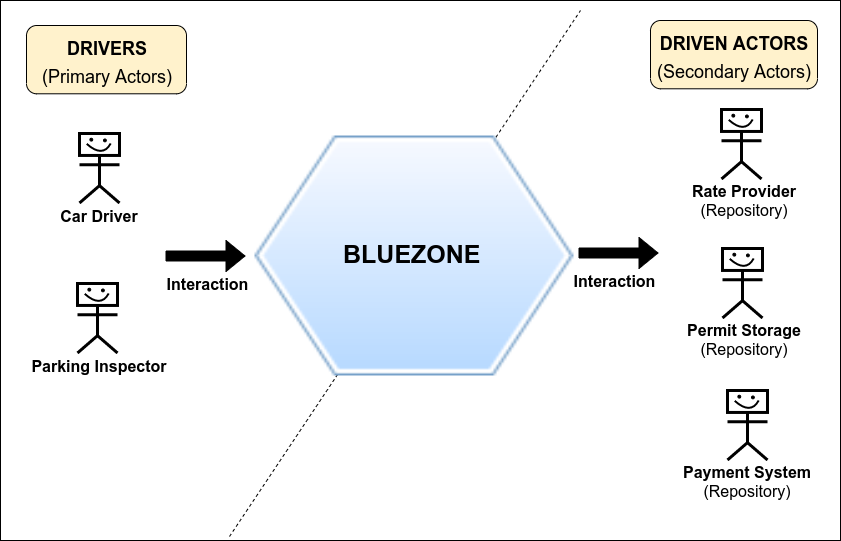

In the example application, BlueZone, the real world things we can identify are:

- Human users: Car driver, Parking inspector.

- Rate files.

- Permit database.

- Remote payment system.

At this early stage of development we don’t care if actors are humans, files, databases, remote systems, etc. We just abstract the actor as a thing outside the application, it doesn’t matter the technology it uses.

So we have the actors shown in Figure 1. Here I borrow a picture for representing actors, drawn by Alistair Cockburn in his talk Alistair in the Hexagone, meaning that an actor can be a human being, a computer, or whatever… it doesn’t matter.

Figure 1: Hexagon and Actors

3.2.- IDENTIFY PORTS

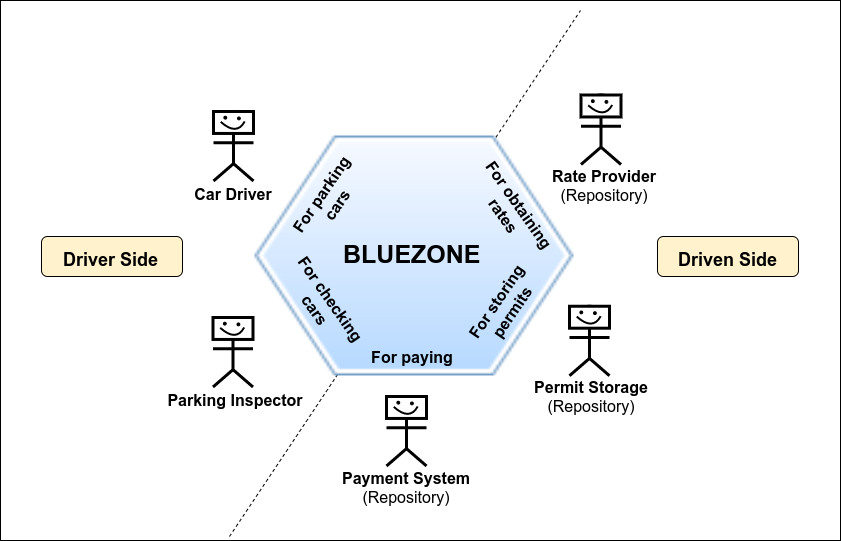

Actors interacts with the hexagon through ports. A port groups the allowed interactions of the hexagon with a set of possible actors according to the purpose of the communication, using an declared program interface (API) which will be independent from the technologies any of the actors might use. An application port has a purpose, it is “for doing something”, and we should name ports that way, even in source code.

- Driver ports: For each driver actor, ask to yourself: What purpose does the driver actor want the application for? The answer will be the name of the port.

In the example application:- Car drivers want the application for parking their cars. So there will be a driver port named “for parking cars”.

- Parking inspectors want the application for checking cars. So there will be a driver port named “for checking cars”.

- Driven ports: For each driven actor, ask to yourself: What purpose does the application want the driven actor for? The answer will be the name of the port. Do this considering the driven actors as abstract repositories/recipients, regardless of their techonology.

In the example application:- The application wants the “Rate Provider” for obtaining rates, in order to calculate prices of parking permits. So there will be a driven port named “for obtaining rates”. The application will just say to the driven port: “Hey you! Gimme the rate of name …”, but it doesn’t care if it comes from a file, or from another application, or from whatever device else.

- The application wants the “Permit Storage” for storing the parking permits that car drivers request, and for querying them when parking inspectors want to check a car. So there will be a driven port named “for storing permits”.

- The application wants the “Payment System” for letting car drivers pay. So there will be a driven port named “for paying”.

Maybe at this early stage of development, you still don’t know all driven actors needed by the application. But don’t worry about it, they will appear when you implement the business logic. You will realize that the application has to deal with some technologic device, or it has to use a functionality which is not under its responsability. In such a case you will have to abstract the purpose of the communication, and create a driven port for it, which should be named according to the “for doing something” pattern.

Figure 2 shows the identified ports added to the drawing. I write the name of the ports inside the hexagon to remark that they are part of it, they belong to the hexagon.

Figure 2: Hexagon with Ports

3.3.- ADD ADAPTERS

Do you remember when I said forget about technologies? Think of an actor as an abstract thing outside the hexagon? Well now it’s time for technologies, forget about abstractions.

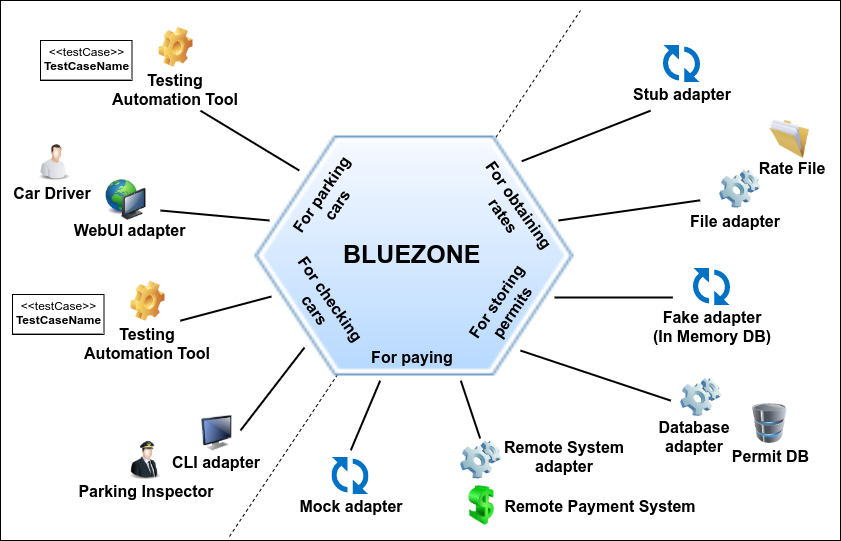

By now we have the hexagon with its ports, and actors outside. Actors are real world devices using a technology. Ports don’t know about technologies. So we have to add adapters for the different technologies that actors use to interact with a port.

For every port, we will have at least two adapters:

- What I call the “Default adapter”: It is the one that will be used when we want to test the hexagon in isolation.

- In the driver side, the default adapter for a port is a testing automation tool that will run test cases against the port.

- In the driven side, the default adapter for a port is a test double. There are many kinds of test doubles: mocks, fakes, stubs, etc. A resource I recommend about this topic is “XUnit Test Patterns” by Gerard Meszaros.

- What I call the “Real adapter”: It is the one that will be used when running the application in production environment.

In the example application we have the adapters you can see in Figure 3.

Then, more adapters could be added if we needed to. For example, if requirements change and users were allowed to access the application from a mobile app, we could add REST API adapters.

Design alternatives for the driver side:

I’ve chosen the design of Figure 3 for showing how to implement an application with multiple driver ports, adapters and actors, but of course there are other ways to design it. I mention here two of them if someone want to try:

-

Imagine that the requirements say that both driver actors (car drivers and parking inspectors) use just one web UI to access the application. Here the trick is to consider those actors as roles that a person can play. We would just have one actor (the person) playing two roles (car driver and parking inspector). There would be two web UI adapters, one for each port. A middleware component would route the web UI request to one of the adapters, depending on the requested operation. In this case ports would have to check the role of the user who did the request.

-

Having just one port instead of two. The port would be kind of a “use case bus”. The hexagon would have use case handlers. This would be analog to a command bus, but instead of commands you would have use cases with a request and a response. This almost deserves an article on its own. Maybe the next one after this series.

3.4.- THE WHOLE PICTURE

Putting it all together, we have the following design diagram that shows all the elements of the system: hexagon (with ports), actors and adapters. It will be a reference for next chapter, where we will see the project structure and dependencies between elements.

Figure 3: Hexagon (with Ports), Adapters and Actors

3.5.- DRIVER PORTS

Finally, to implement the business logic in the next chapters, we need to define now the API of the hexagon, i.e. the operations offered by driver ports to the outside world.

A port groups a set of operations related to the purpose of the port. For every driver port, do the following:

- Write down the sequence of interactions that take place when a driver actor uses the port. These interactions will help you to find out the operations that the port should offer.

- Identify and write down the names of the operations you found.

- For every operation, describe the input it receives, the output it returns, and what it does.

Once you’ve done this, you will have defined the API of the hexagon.

Here I will put the API definition in Java, but you can do it in natural language, since this is just the contract design.

In the example application:

“for parking cars” port:

-

Interactions of the actor (A) with the port (P):

A: Requests a parking permit

P: Returns all the rates indexed by name

A: Enters the car plate, the rate name, the ending datetime of the period, and the payment card

P: Issues the parking permit -

Operations of the port:

getAllRatesByName, issuePermit -

Description of the operations:

public interface ForParkingCars {

/**

* Returns the information of all the available rates in the city.

*

* @return a map of RateData objects, indexed by rate name. @see RateInfo

*/

public Map<String, RateData> getAllRatesByName();

/**

* Issues a permit for a car parked at a regulated area, valid until a datetime, paying it with a card.

* Returns a ticket with the permit information.

*

* First the permit price is calculated, depending on the number of minutes of the permit period,

* according to the rate of the area where the car is parked at.

* Then, permit price is charged to the payment card.

* And finally the permit is stored.

*

* @param clock Clock to get current datetime from, since it will be the starting datetime of the permit period

*

* @param permitRequest DTO with the info needed for issuing the permit. @see PermitRequest

*

* @return permitTicket DTO with the info of the issued permit. @see PermitTicket

*/

public PermitTicket issuePermit ( Clock clock, PermitRequest permitRequest );

}

Definition of the data that port operations manage:

public class RateData {

private String name;

private MoneyDto costPerHour;

private int minMinutesAllowed;

private int maxMinutesAllowed;

private TimeTableDto timetable;

...

}

public class MoneyDto {

private BigDecimal amount;

private String currencySymbol;

...

}

public class TimeTableDto {

private Map<DayOfWeek,List<TimeIntervalDto>> intervalsByDayOfWeek;

...

}

public class TimeIntervalDto {

private LocalTime minTime;

private LocalTime maxTime;

...

}

/**

* DTO class with the input needed for issuing a permit:

* carPlate Plate of the car to get the permit for

* rateName Rate name of the regulated area where the car will be parked at

* endingDateTime Expiration datetime of the permit period

* paymentCard Data of the card to charge the permit price to. @see PaymentCardData

*/

public class PermitRequest {

private String carPlate;

private String rateName;

private LocalDateTime endingDateTime;

private PaymentCardData paymentCard;

...

}

/**

* DTO class with information about a payment card:

* number 16 digits

* cvv Card verification value (3 digits)

* expirationDate Year and month from which the card will no longer be valid

*/

public class PaymentCardData {

private String number;

private String cvv;

private YearMonth expirationDate;

...

}

/**

* DTO class with the output returned when issuing a permit:

* code Unique identifier of the permit

* carPlate Plate of the car the permit has been issued for

* startingDateTime When the permit period begins

* endingDateTime When the permit period expires

* rateName Rate name of the regulated area where the car is parked at

* price Amount of money payed for the permit

*/

public class PermitTicket {

private String code;

private String carPlate;

private LocalDateTime startingDateTime;

private LocalDateTime endingDateTime;

private String rateName;

private MoneyDto price;

...

}

“for checking cars” port:

-

Interactions of the actor (A) with the port (P):

A: Enters the car plate and the rate name

P: Checks whether the car is illegally parked -

Operations of the port:

illegallyParkedCar -

Description of the operations:

public interface ForCheckingCars {

/**

* Checks whether a car parked at a regulated area doesn't have any active permit.

* A permit is active if the current datetime is before the ending datetime of the permit period.

*

* @param clock Clock to get current datetime from

* @param carPlate Car plate of the car that we want to check

* @param rateName Rate name of the regulated area where the car to check is parked at

* @return true if the car doesn't have any active permit for the rate, false otherwise

*/

public boolean illegallyParkedCar ( Clock clock, String carPlate, String rateName );

}

I want to remark here that the clock as a parameter is useful for mocking the current datetime when testing. But if you have many methods that need the clock, it has the drawback that you should pass it to all of them. To avoid this, it would be better to create a driven port for the clock.

4.- ANALOGY WITH USE CASES

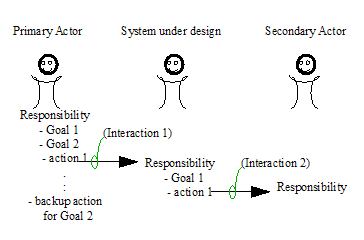

It is worth to mention here the paralelism between hexagonal architecture and use cases world.

Reading the article “Structuring use cases with goals” by Alistair Cockburn, I realized that hexagonal architecture is tightly related to use cases. I describe here some analogies I’ve found:

-

In use cases there are different levels of abstraction for goals: summary goals, user goals (sea level) and subfunctions. At high level (summary goals) you have multiple primary actors. This is for helping you to find out better the functionality that the system might offer to the users. Then at lower levels (user goals and subfunctions) you have just one actor.

In hexagonal architecture, the hexagon (the application) as a whole is needed to achieve summary goals, and it is used by multiple driver actors. Then driver ports are at a lower level, for achieving user goals. And subfunctions are operations of a driver port.

A topic related to this is “How primary actors can be important and unimportant at the same time”, that Alistair Cockburn explains in his book “Writing effective use cases”. -

In use cases we have this figure, that shows how actors communicate with a “goal - interaction - responsability” chain:

Figure 4: Actor-to-actor communication model

Hexagonal architecture fit this model: Driver actors are primary actors, the hexagon (the application) is the “system under design”, and driven actors are secondary actors. Driver ports group use cases.

Actors have responsabilities, which are performed by fixing goals. To achieve a goal, the actor has to do some actions. An action triggers the interaction with another actor. This interaction is a call to the other actor responsability. And so on.

In hexagonal architecture, interactions link driver actor goals with application responsabilities. The operations that the application offer at a driver port are application responsabilities related to the purpose of the port.

So the application is structured grouping responsabilities in ports acording to a purpose, which is the actor goal.

In the right side of the hexagon… To perform its responsabilities, the hexagon will have to achieve goals. For achieving these goals it might need to interact with external systems (driven actors) through driven ports. These interactions link application goals with driven actor responsabilies.

The hexagon would be like any other actor. It has goals and to achieve them it might need to interact with another actor.

REMARK:

I want to quote here Dr. Alistair Cockburn, when I asked him in an interview what could he tell us about the “Hexagonal Architecture - Use Cases” relationship, whether I am right, or should I change anything I wrote about this topic. He answered the following:

« The driver/driven = primary/secondary distinction is correct. The goal levels less so. A sea-level or user-task-level use case roughly speaking represents one business atomic transaction, quite possible a database “transaction” in database terms (meaning fully committed or fully rolled back). However, every function call on a port is a use case, and probably a fish-level or even clam-level use case from a human’s point of view. A new function call might only add a small piece of information or answer a small question needed to reach the full business transaction.

It might be that a port aggregates one-person summary level use case, but it’s possible that they summary level use case involves multiple people hitting multiple ports. The purpose of a summary level use case is to show the macro flow, so there is no reason to expect them to stay on one port. Something needs to show how all the hits to the system over time add up to something interesting from the human or business perspective.»

I want to thank Alistair Cockburn for his attention and his comments. You can read the entire interview at https://jmgarridopaz.github.io/content/interviewalistair.html

5.- LINKS

- Hexagonal Architecture resources:

https://jmgarridopaz.github.io/content/resources.html

- “XUnit Test Patterns”, by Gerard Meszaros:

- “Structuring use cases with goals”, an article by Alistair Cockburn: