Hexagonal Architecture

An implementation guide

Chapter 2: PROJECT STRUCTURE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Introduction

- Source code organization

2.1. One module for the hexagon

2.2. One module for each adapter

2.3. One module for application startup - Dependencies

- Modules vs Layers

- Links

1.- INTRODUCTION

This is the second article of a series showing how to implement an application according to Hexagonal Architecture, also known as Ports and Adapters pattern, whose author is Dr. Alistair Cockburn.

The example application is called BlueZone, and it is described and designed in Chapter 1.

The pattern definition doesn’t say anything about how to implement the architecture. My vision of Hexagonal Architecture is modular, with the hexagon at the center, and adapters around it, belonging to no layer, each one attached to a port of the hexagon. The different adapters depending on a port stand for different swappable technologies that the actor communicating with the hexagon might use.

In this chapter we will see how to organize the source code in modules using Java 9, dependencies between modules (“who knows of whom”), and how to configure those dependencies.

2.- SOURCE CODE ORGANIZATION

The code base of the example application is at BlueZone GitHub repository.

The whole project is structured in modules. In Java 9, a module is a set of packages, that you can compile apart generating a jar file. Modules depend on each other.

Regarding Java 9 modules, I highly recommend the book “Java 9 Modularity: Patterns and practices for developing maintainable applications”, by Sander Mak & Paul Bakker

I’ve put all the modules in just one GitHub repository, so that you can see and build them all together, but Java 9 allows you to have them in different repositories, compile them apart, and then provide their locations at runtime to choose them dynamically. We will see this later on, at the end of this article series, as an advanced way of execution.

Now let’s see the modules and the convention I follow for naming them and their packages.

The important thing with this way of naming modules, is that when we see a module name at first glance, we know whether it is business logic or it deals with real world technology, since the first word after the application name is either “hexagon” or “adapter”.

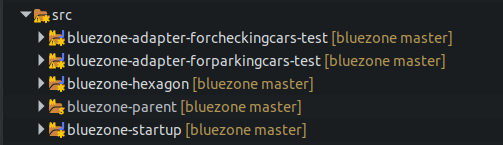

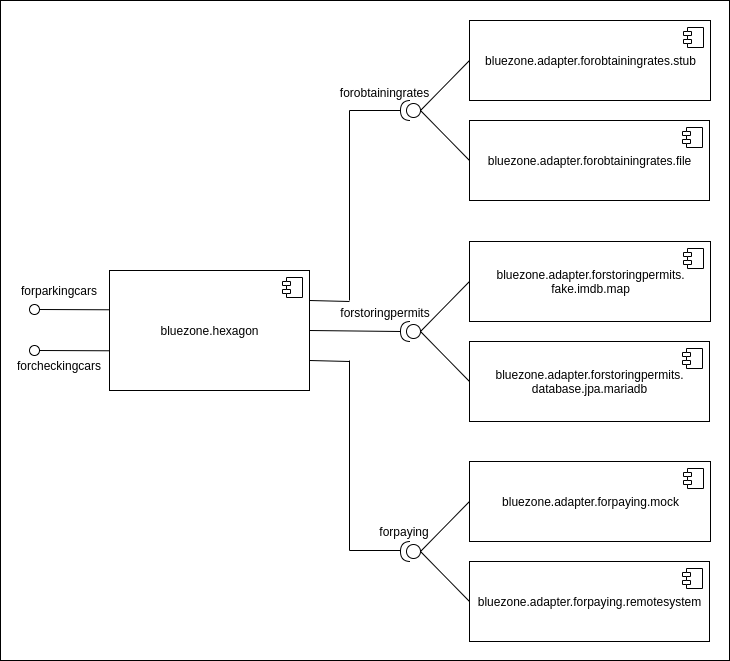

Figure 1: Modules naming convention (*)

(*) bluezone-parent is a maven configuration module, nothing to do with a Java 9 source code module

2.1.- ONE MODULE FOR THE HEXAGON, with name: <app_name>.hexagon

Hexagonal Architecture pattern says nothing about how to structure the source code of the hexagon. The pattern just says that the hexagon offers “ports” to the outside world, for allowing external actors to interact with the hexagon.

So how do we “publish” an interface (the port) of a module (the hexagon)?

Before Java 9, a public type was visible to the rest of the world. Now, with modules, a public type is just visible inside its module. For other modules to see the public type, you have to export the package the type belongs to. Exporting a package would be like “publishing” its public types to the outside world.

So we will have a package for each port of the hexagon. A package for a port contains a public interface defining the port operations, and public data types that those operations manage.

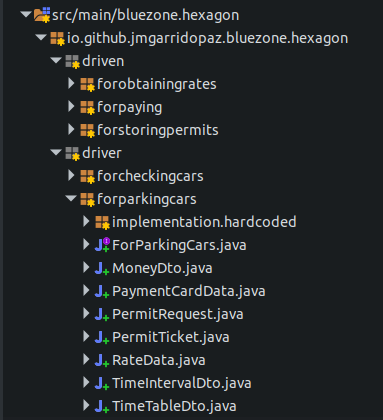

Figure 2: Ports packages in hexagon module

The name of a package for a port will be:

<reverse_domain_name>.<app_name>.hexagon.<side>.<port_name>

This way ports are grouped by their side (driver/driven), so that we see at a first glance whether the port is driver or driven. This is important, since driver ports operations are called by an adapter, while driven port operations are implemented by an adapter. It’s the left/right asymmetry .

In the example application, the name of the hexagon module is

bluezone.hexagon

which has 5 packages for its ports (2 driver and 3 driven):

package io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.hexagon.driver.forparkingcars;

package io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.hexagon.driver.forcheckingcars;

package io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.hexagon.driven.forobtainingrates;

package io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.hexagon.driven.forstoringpermits;

package io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.hexagon.driven.forpaying;

Ports are named following the forDoingSomething pattern, saying what they are for, in a technology agnostic way from the application point of view, i.e. no matter the technology of the actor that is behind the port.

=====

The business logic (hexagon source code) organization fall out of the scope of Hexagonal Architecture pattern. It will be a set of Java classes, types, etc implementing the operations defined at driver port interfaces, and calling operations on driven port interfaces. But you can structure this source code however you want to, it is not a Hexagonal Architecture issue.

As an example, the simplest way in Java to implement a hexagon would be just one class, implementing driver port interfaces, and depending on driven port interfaces (constructor arguments).

public class BusinessLogic implements ForParkingCars, ForCheckingCars {

private final ForObtainingRates forObtainingRates;

private final ForStoringPermits forStoringPermits;

private final ForPaying forPaying;

public BusinessLogic ( ForObtainingRates forObtainingRates, ForStoringPermits forStoringPermits, ForPaying forPaying ) {

this.forObtainingRates = forObtainingRates;

this.forStoringPermits = forStoringPermits;

this.forPaying = forPaying;

}

@Override

public Map<String,RateData> getAllRatesByName() {

// Implement the driver port operation calling driven ports operations

}

// ...

A usual way of structuring the hexagon is to split it into two layers: application and domain, following DDD (Domain Driven Design) rules, but this has nothing to do with Hexagonal Architecture.

=====

2.2.- ONE MODULE FOR EACH ADAPTER, with name <app_name>.adapter.<port_name>.<technology>

This stands for a module containing an adapter for an actor using the <technology> in the interaction with the hexagon at <port_name> port. The <technology> part could be as specific and long as you want.

For example:

<app_name>.adapter.<port_name>.webui

is an adapter for an actor that interacts with <port_name> port using a web UI. We could be more specific and say more about the technology. For example, if we are using the Spring Framework, we could have named the adapter:

<app_name>.adapter.<port_name>.webui.spring

If then we develop another web adapter using the Tapestry Framework:

<app_name>.adapter.<port_name>.webui.tapestry

Other examples of technology naming could be:

<app_name>.adapter.<port_name>.test.cucumber

<app_name>.adapter.<port_name>.database.sql.orm.jpa

<app_name>.adapter.<port_name>.database.mongo

<app_name>.adapter.<port_name>.file

<app_name>.adapter.<port_name>.stub

You can observe that with this naming convention we don’t say anywhere whether the adapter is either driver or driven. We don’t need to, since that’s something that comes with the port. The port of the hexagon is either driver or driven, and so will be the adapter.

In our example application, we are going to develop 2 adapters for each port:

Driver adapters:

bluezone.adapter.forparkingcars.test

bluezone.adapter.forparkingcars.webui

bluezone.adapter.forcheckingcars.test

bluezone.adapter.forcheckingcars.cli

Driven adapters:

bluezone.adapter.forobtainingrates.stub

bluezone.adapter.forobtainingrates.file

bluezone.adapter.forstoringpermits.fake.imdb.map

bluezone.adapter.forstoringpermits.database.jpa.mariadb

bluezone.adapter.forpaying.mock

bluezone.adapter.forpaying.remotesystem

The root package for the source code of an adapter would be:

package <reverse_domain_name>.<app_name>.adapter.<port_name>.<technology>

2.3.- ONE MODULE FOR APPLICATION STARTUP, with name: <app_name>.startup

This module is the entry point to the application.

You can run the application by running any of the driver adapters, so there will be a package for each driver adapter, containing the source code needed for instantiating the different components of the architecture, wiring them up, and running the driver adapter.

package io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.startup.forparkingcars.test;

package io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.startup.forparkingcars.webui;

package io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.startup.forcheckingcars.test;

package io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.startup.forcheckingcars.cli;

During my researching on hexagonal architecture, I’ve studied several techniques for implementing the application startup, and I will show them in detail along the next articles in these series.

3.- DEPENDENCIES.

Rules about dependencies between modules are easy:

-

The hexagon module depends on nothing.

- An adapter module for an actor communicating with the hexagon at a port, depends on:

- The hexagon.

- The technology used by the actor.

- The startup module depends on the hexagon and all the adapters.

Regarding to dependencies, in Java 9 every module has a definition file (module-info.java) where it declares:

- The modules it “depends on” (requires).

- The packages it “publishes” (exports) to other modules.

So let’s see the module-info.java file of the modules:

THE HEXAGON MODULE.

It contains the business logic, including ports. The hexagon is decoupled from any technology, i.e. from the adapters. If we modify the adapters, the hexagon shouldn’t care, so it doesn’t require (depend on) any module, maybe just some library module with utilities of the programming language if you will.

module bluezone.hexagon {

// driver ports

exports io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.hexagon.driver.forparkingcars;

exports io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.hexagon.driver.forcheckingcars;

// driven ports

exports io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.hexagon.driven.forobtainingrates;

exports io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.hexagon.driven.forstoringpermits;

exports io.github.jmgarridopaz.bluezone.hexagon.driven.forpaying;

...

...

}

It publishes (exports) the packages with the ports. Each port package just publishes the interface defining port operations, and the data types that those operations manage. Any logic implementing the driver ports is hidden to other modules. It is also possible to declare the modules you want to export a package to, so that you could export a port just to its adapters. But we would have to change this file and recompile the hexagon, every time we add a new adapter.

THE ADAPTERS MODULES.

An adapter module for a port, requires the hexagon module, and other modules related to libraries and frameworks, according to the technology that the actor behind the port is using.

For example, the definition file for bluezone.adapter.forparkingcars.test module is:

module bluezone.adapter.forparkingcars.test {

/*

* DEPENDENCIES: Hexagon, libs, test framework

*/

requires bluezone.hexagon;

requires io.github.jmgarridopaz.lib.portsadapters;

requires io.cucumber.java;

requires junit;

requires io.cucumber.datatable;

requires io.cucumber.core;

...

}

We can see that it requires the hexagon module, since it uses forparkingcars port, and it also requires modules about “cucumber”, which is the specific technology used by the actor (test cases).

io.github.jmgarridopaz.lib.portsadapters module is a library of my own, where I define types regarding hexagonal architecture.

THE STARTUP MODULE.

It builds the application and runs it, so it needs access to all modules: hexagon and adapters.

module bluezone.startup {

/*

* Depends on all the other modules: hexagon and adapters

*/

requires bluezone.hexagon;

requires bluezone.adapter.forparkingcars.test;

requires bluezone.adapter.forcheckingcars.test;

...

}

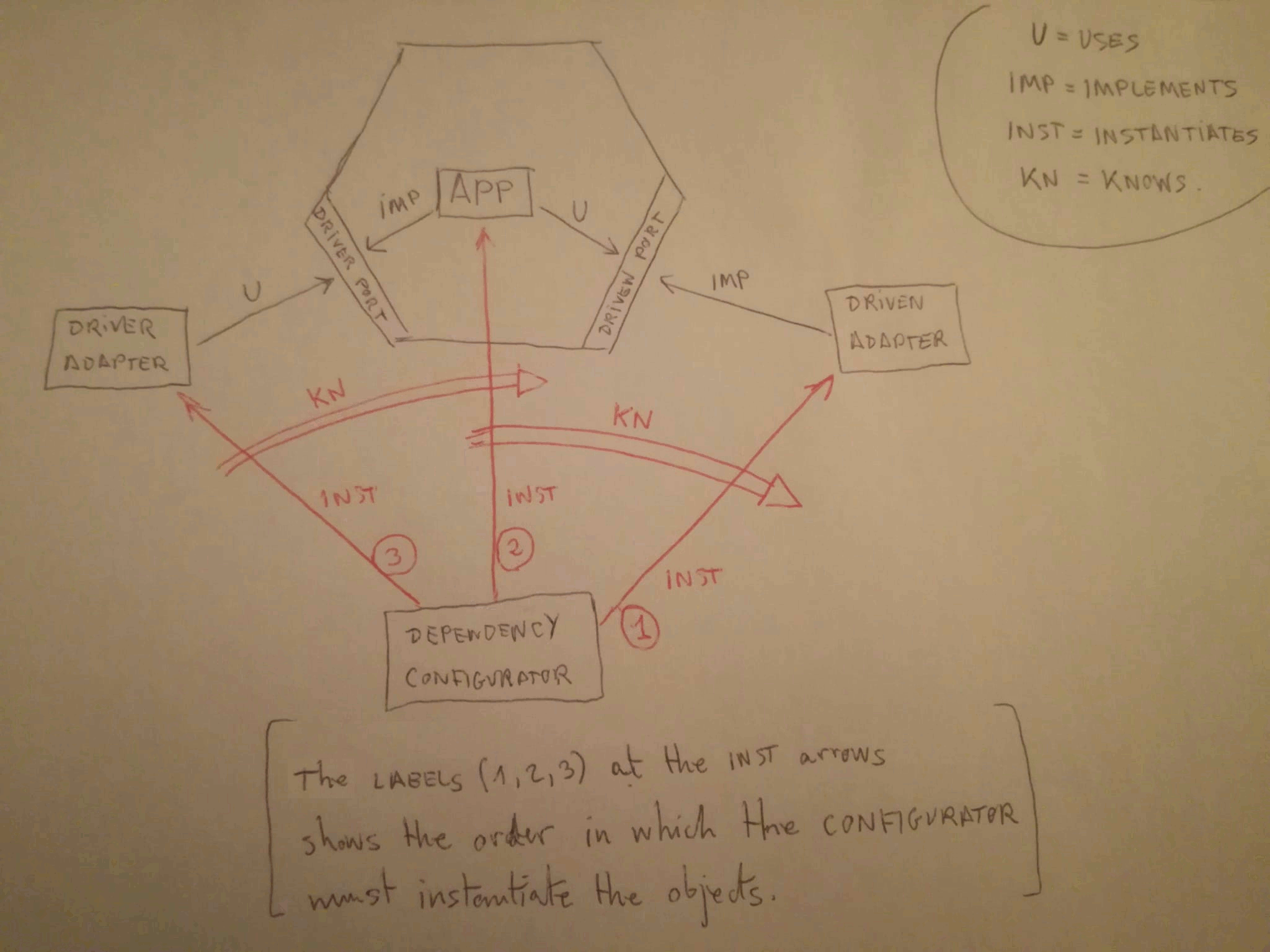

This module configures the dependencies between the hexagon and the adapters, applying the Configurable Dependency Pattern at both driven and driver side, following these steps:

- For each driven port, instantiates a driven adapter, which implements the driven port interface.

- Apply Configurable Dependency Pattern on driven side: Instantiate the hexagon class, which knows of driven ports, and implements a driver port interface.

- Apply Configurable Dependency Pattern on driver side: Instantiate a driver adapter, which knows of the driver port of the hexagon.

- Run the driver adapter.

Here is a hand-drawn diagram I made once about this topic:

Figure 3: Dependency Configurator in Startup Module

I offered this picture to Alistair Cockburn, who published it on Twitter: https://twitter.com/TotherAlistair/status/1122918489558278145

At either driver or driven side, the Configurable Dependency Pattern applies as follows, quoting Alistair Cockburn in his “Alistair in the Hexagone” talk:

The one who does the triggering has to know the dependency.

So at driver side, a driver adapter depends on an abstraction of the hexagon (a driver port):

public abstract class DriverAdapter<T> {

private final T driverPort;

protected DriverAdapter ( T driverPort ) {

this.driverPort = driverPort;

}

protected T driverPort() {

return this.driverPort;

}

public abstract void run ( String[] args );

}

And at driven side, the hexagon depends on an abstraction of the driven adapter (a driven port):

public class BusinessLogic implements ForParkingCars, ForCheckingCars {

private final ForObtainingRates forObtainingRates;

private final ForStoringPermits forStoringPermits;

private final ForPaying forPaying;

public BusinessLogic ( ForObtainingRates forObtainingRates, ForStoringPermits forStoringPermits, ForPaying forPaying ) {

this.forObtainingRates = forObtainingRates;

this.forStoringPermits = forStoringPermits;

this.forPaying = forPaying;

}

// ...

4.- MODULES vs LAYERS.

Hexagonal Architecture is an object structural pattern, it is not an architecture style.

So it is not layered “per se”, it is not component-based (modular) “per se”, etc. It is whatever you want it to be, in the sense that the architecture style you use is an implementation detail that the pattern doesn’t fix. You can implement it using any architecture style, as long as it fits the structure and relationship rules of the pattern.

For example, I see two architecture styles we can implement the pattern with:

- Modular: This is the approach I follow in these article series, as we have just seen in the previous sections.

- One module for the hexagon.

- One module for each adapter.

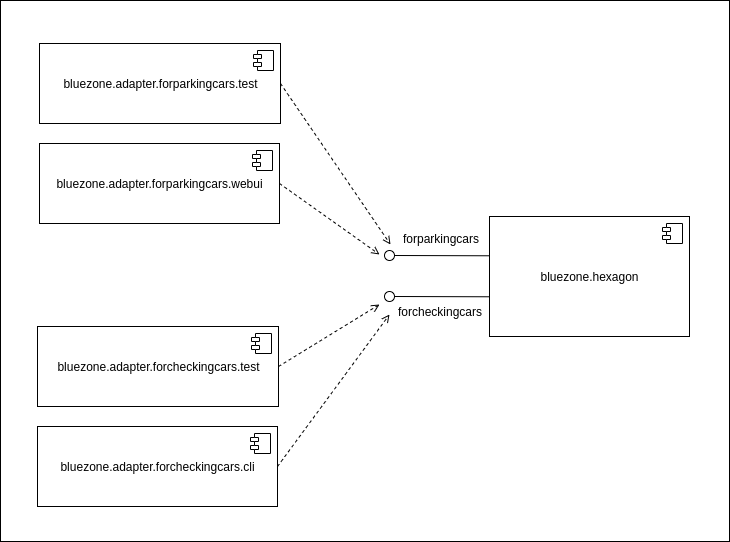

The modular diagram is similar to an UML component diagram. The hexagon module would look like a component where driver ports are “provided interfaces”, and driven ports are “required interfaces”:

Figure 4a: Modular Diagram (Driver Side)

Figure 4b: Modular Diagram (Driven Side)

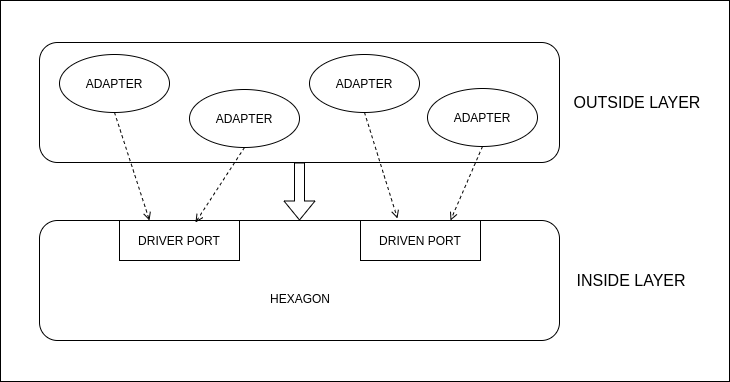

- Layered: It splits source code into two layers (inside vs outside), with just a dependency rule: “outside” depends on “inside”.

- Inside layer: the hexagon.

- Outside layer: all the adapters.

Figure 5: Layered Diagram

These two layers would be in fact three, since the startup module can be considered here as another layer on top of the outside layer.

I see the modular approach more flexible, since we can add adapters dynamically, without having to recompile the other adapters in the layer.

Whatever approach you choose, there are some key concepts to consider for fitting Hexagonal Architecture pattern rules, which make it different from Onion:

-

Ports are not a layer themselves. Ports are part of the hexagon, they are interfaces that belong to the business logic of the application, i.e. to the hexagon. In Java 9, ports are interfaces into packages that the hexagon module publishes to other modules. The other packages are hidden to the outside world.

-

An adapter depends on the hexagon at one of its ports. An adapter is a piece of software playing a role (driver/driven) against a port. A driver adapter will be a Java class that “uses” a driver port interface, and a driven adapter will be a class that “implements” a driven port interface. In Java, this is achieved by using generic types. For example, a driver adapter is a generic class with one type parameter, which is the driver port interface that it uses. Whether an adapter plays different roles: it drives more than one port; or it is driven by more than one port; or it is driven by a hexagon port and it drives a port of another hexagon… it’s up to you, but then you should know that you are not following the SRP (Single Responsability Principle).

-

Adapters are independent from each other. An adapter doesn’t know of the others, it just depends on the hexagon, and on the actor whose technology it is adapting (for example a database). But an adapter shouldn’t be able to access another adapters. This is why if we go for the two layers implementation, we should care about protecting visibility between adapters, since a layered architecture allows a component to access other components in the same layer. In Java, we have the default access modifier (package-private), which makes a type visible to just the members in the same package. So you should have a package for each adapter, and make types in each package not accessible from others, i.e. make them package-private.

5.- LINKS

- Hexagonal Architecture resources:

https://jmgarridopaz.github.io/content/resources.html

- “Java 9 Modularity” book. Authors: Sander Mak & Paul Bakker. Publisher: O’Reilly

- “Hexagonal != Layers”, by Thomas Pierrain:

https://tpierrain.blogspot.com/2016/04/hexagonal-layers.html

- “The key ring metaphor: A three steps initialization” (pdf, page 11), by Thomas Pierrain:

https://github.com/tpierrain/hexagonalThis/blob/master/Hexagonal.pdf